Kakadu in Crocodile Dundee Film

Take a Self Guided Tour in the Footsteps of Crocodile Dundee

Follow in the footsteps of Australia’s most famous outback rogue, Mick Dundee, with this self-guided tour of the film’s most iconic Kakadu locations

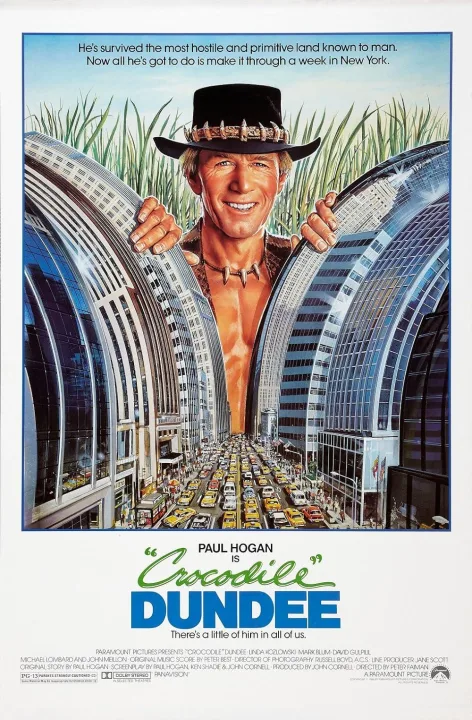

On 30 April 1986, Crocodile Dundee received its premier screening in Sydney, contributing to the rapid evolution of Northern Territory cultural and adventure tourism.

Film locations on google maps

|  |

'The Croc' Hotel built in the legacy of Crocodile Dundee

The film was a massive success, grossing over $328 million worldwide shining a spotlight on Australia’s unique outback and larrikin culture.

For Kakadu, a fledgling tourism industry was supercharged overnight, with the now legendary Crocodile Hotel being built as a result of the new interest in the destination.

Developed by the local Indigenous Gagudju people, the Crocodile Hotel highlighted the power of the ‘crocodile’ in marketing the region, with nearby Yellow Water Billabong established as one of the most popular locations for cruises so that visitors could catch sight of ‘salties’ in their natural habitat. Yellow Water starred in the croc-horror film Rogue three decades later.

While crocodiles may have had a fearsome reputation in the wild, Crocodile Dundee converted the reptiles into one of Australia’s biggest tourism drawcards.

Crocodiles certainly took centre stage in Crocodile Dundee. They feature in the film almost from the start as American journalist Sue Charlton comes to Kakadu in search of a bushman reported to have lost half a leg to a saltwater crocodile.

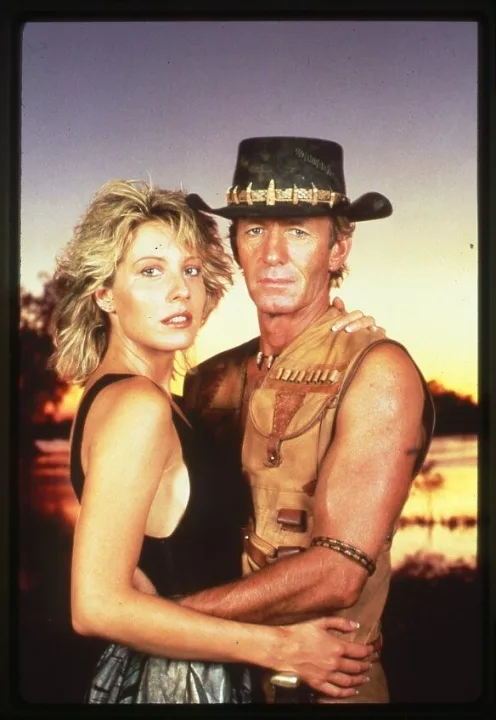

Sue Charlton, played by American actor Linda Kozlowski, arrives at ‘Walkabout Creek’ and her first encounter with ‘Mick’ Dundee (played by Paul Hogan) is when he announces his arrival at the pub she is staying by throwing his hunting knife at the bar and wrestling a stuffed dead crocodile.

While Sue finds that he hadn’t lost his leg, she does find lots of outback action, involving kangaroo shooters, snakes, buffaloes and, of course, crocodiles.

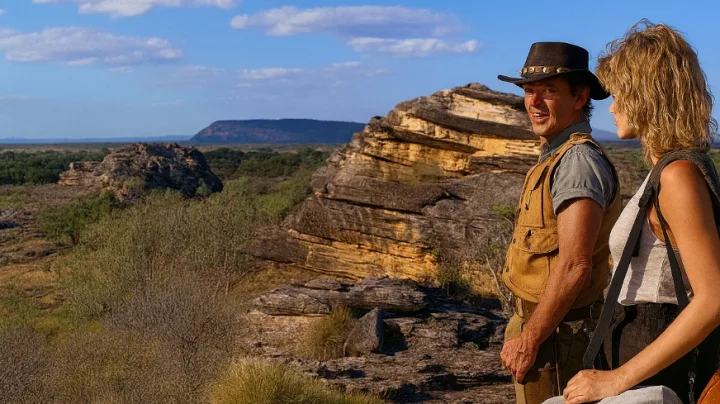

Mick decides to show Sue his country, and this is where the audience gets to see the spectacular Kakadu scenery.

Follow in Mick and Sue’s footsteps through this scene-by-scene guide to Kakadu’s main locations in the two Crocodile Dundee films.

Crocodile Dundee Film Locations: Kakadu

1. Ubirr Rock Art Site

Ubirr is the rock formation in Kakadu National Park where Mick Dundee climbs to the top, points toward the horizon, and says "This is my backyard and over there is the Never Never" while the movie camera panned across the flood plain.

|  |

One of the icons of Kakadu, Ubirr's galleries contain the world's most panoramic sweep of history with drawings ranging from the thylacine to arrival of Europeans.

An easy 40 minutes’ drive from Jabiru, visitors can climb Ubirr for most of the year, with guided tours available during the dry season. The sunset at Ubirr is one of the most popular times to visit.

2. Road from Jabiru to Gunbalanya via Cahills Crossing

Mick and Sue head further into the bush but are stopped by a water buffalo that refuses to budge. The scene was shot on the road between Jabiru and Gunbalanya, with Mick solving the impasse by hypnotising the water buffalo.

While Cahills Crossing doesn’t appear on screen, anyone travelling this route today will pass through one of Kakadu’s most iconic locations. Cahills Crossing spans the East Alligator River and is the only road access to Gunbalanya, cutting across vast floodplains with birdlife — and known for frequent sightings of saltwater crocodiles.

3. Anbangbang Billabong & Burrungkuy (Nourlangie) Rock Art Site

Mick and Sue then head into the bush for their first night of adventure. This takes them to Angbangbang Billabong, where Mick is given the opportunity to demonstrate his bush skills, including a clever ruse where he pretends to shave with his massive sharp bladed knife.

‘Mick’s country’ includes spectacular footage of Angbanglang Billabong where crocodiles and birdlife are featured, along with the very distinctive Nourlangie Rock (Burrungkuy) in the background.

Nourlangie is one of the prime cultural tourism sites in Kakadu, home to important Aboriginal rock-art “galleries”. It is estimated that Aboriginal people have been using this site for over 60,000 years. The entire area is archaeologically important, as it is believed that this is where the earliest tropical settlement of Australia occurred. The people in this area developed grinding stones for crushing seeds and later used the grinding stones to crush ochre for painting.

Nourlangie Rock and surrounding early art sites are among the reasons Kakadu National Park was made a World Heritage Site. The richness of the ecosystems here is another reason for protecting the area.

After being offended by Mick's assertion that as a "sheila" she is incapable of surviving the outback alone, Sue heads off into Kakadu, where she stops at a billabong to refill her water bottle only to be attacked by a crocodile. Fortunately, Mick had been following her and was on hand to wrestle with and kill the croc, thereby justifying his ‘Crocodile’ tag.

This scene is actually filmed just outside Darwin in Girraween Lagoon, and with a mechanical crocodile – though originally Paul Hogan (supposedly) contemplated wrestling a real croc.

4. Gunlom Falls

Gunlom Falls (called Echo Lake in the film) is the location where Mick Dundee spears a fish and cooks a goanna as part of a bush tucker BBQ.

Prior to the film, Gunlom Falls was known as UDP Falls (after the Uranium Developing and Prospecting Company) and was a popular place for prospectors to swim in the 1960s. In the Crocodile Dundee movie, it is referred to as Echo Lake.

After Mick cooks dinner, Mick and Sue go swimming in the spectacular Gunlom rock pool, now one of the favourite tourist locations in Kakadu.

5. Bardedjilidji Walk (Crocodile Dundee II)

Kakadu had a major reprise in the second Crocodile Dundee film. Filming took place in areas around Ubirr and Bardedjilidji, a walking trail named after the local Aboriginal word for “walking”. The Bardedjilidji Walk is a scenic, relatively short (2.5km) trail near the East Alligator River known for sandstone formations, paperbark forests, rock art, and the cave featured in Crocodile Dundee II where Mick Dundee holds drug cartel members.

Along the walk you'll find a number of unique habitats, ranging from freshwater swamps and billabongs to sandstone formations that were once believed to be islands during prehistoric times. The cave is home to bats, geckos and insects, as well as some hard to spot aboriginal rock art.

6. Oenpelli Road (Crocodile Dundee II)

The famous ‘bush telephone’ scene was shot at the rock escarpment a couple of kms north of the Ja Ja camp turn off, on the eastern side of the Oenpelli road. When you drive north along the Oenpelli Road you will see it on your right.

The scene involves Mick using an Aboriginal ‘bullroarer’ to make a bush ‘telephone call’, calling on help from whoever is nearby. In a convoluted plot, Wally (played by John Meillon) has been captured by an American gang who are trying to lure Mick to their trap. Wally tells the spooked baddies the whirring noise is that of a ferocious bird who can carry away humans.

Film critic, Paul Byrnes, said of the scene:

“The reaction of the animals is like a scene from a Tarzan film of the 1930s, but Mick uses a bullroarer rather than a blood-curdling cry. Nevertheless, the scene isn’t treated as comedy. The slow rise of the camera up the rock to where Mick is framed in the golden light of sunset continues the process of ‘Aboriginalising’ Mick (just as in clip one, where there is a didgeridoo on the soundtrack). The scene is meant to give the film a deeper sense of mysticism, and to suggest forces that are only dimly understood by the uninitiated.”

Crocodile Dundee and Me: Bessie Coleman

Bessie Coleman’s story as told by Mikaela Jade, Parks Australia

A smash box-office hit, ‘Crocodile Dundee’ became a worldwide sensation, but as I find out from Bessie Coleman (senior traditional owner Jawoyn, Bolmo, Matjba and Wurrkbarbar peoples), the film is so much more for her family and other Bininj/Mungguy people.

Here’s how it has permeated Jawoyn culture as a part of their modern dreaming.

“My heart fills with pride when I think of that balanda (white man) and his lady on my Country, at Gunlom. It’s the first time a big film star came and worked with my people, proper way. It was really good for the board to approve that movie. It was our voice,” says Bessie.

She is a born storyteller and while we sit in a cafe in Pine Creek, it’s impossible not be drawn into her world as she recalls the time when Paul Hogan and his crew arrived in Kakadu to film She has a big smile and an infectious laugh when she remembers ‘how good that balanda man was at spearing barramundi’ – even though barramundi were never caught traditionally at Gunlom.

“Gunlom is a special place, and through the movie the world got to see our special places and it brought people to Kakadu. Kakadu got famous from that movie,” she says. Bessie says that she would encourage all film-makers to come back on Country after they make their films. “We get great pride from our Country being in movies. We want to share that with the producers and movie stars when it is all finished,” she said.

Before balanda came to Kakadu, Gunlom was a sacred site where only the old people could visit. It is now one of the most popular visitor areas in Kakadu, and Bessie couldn’t be happier. She enjoys people visiting her Country, and sharing her culture.

“When I first saw the movie, I felt good about it and I still love that movie. I can see my Country, and other Bininj Country in that movie. I spent a lot of time living all over Kakadu, and it’s all in that movie. That’s not Mick Dundee’s Country – that’s my Country, and Jonathan Nadji’s, and Jeffrey Lee’s,” says Bessie, laughing at fact versus fiction.

Bessie spent her life working in Kakadu before it was a national park, and is now a member of the Kakadu National Park Joint Park Management Board.

“I used to go hunting for buffalo with my partner and family, I have been a cultural advisor to the mine, and a seasonal ranger at Gunlom. I have had my whole life looking after this place,” she reflects.

While Bessie loves watching ‘Crocodile Dundee’ for the landscapes, she points the ways in which Paul Hogan and his crew were culturally mindful of her people.

“Those bushfoods were all harvested with our family members, and were foods from the Gunlom area.” Hogan was also instructed on the correct way to spear fish, and use a bull roarer. “He’s very good,” she says with surprise in her voice.

We talk about what the film means to her family.

“My grannies (grandkids) always ask me to watch ‘Crocodile Dundee’ with them. They asked me to buy it for them. Not just the first one, but all of them!”

I wonder why a movie created four generations ago still resonates with Jawoyn. Bessie tells me it’s because her brother and other family are in the film. Having passed away many years ago, the film gives Bessie, her children, and their children’s children a way to connect with her brother and other relatives.

“It reminds me that I had a big brother, and for the kids, they get so much happiness from pointing out their big uncle at the Corroboree.”

Bessie’s only regret is that so few film stars and producers return to Kakadu after filming.

“We would love to see them again,” she says, “Or at least receive a copy of the film!”

Thirty years have gone by since a larrikin Australian ‘had a go’ making a film. Bessie says that in another 30 years Jawoyn will still watch Crocodile Dundee, and remember the time a man fell in love with a lady on the beach at Gunlom.

Although times change, and Bininj/Mungguy people change too, Kakadu remains the same and Gunlom is still as perfect as when the film was made. Kakadu National Park’s World Heritage status means we can all keep falling in love with Kakadu.

The Story Behind Kakadu’s Starring Role

Thirty years ago, the film Crocodile Dundee catapulted Kakadu into the international spotlight. Paul Hogan played the character of Mick ‘Crocodile’ Dundee, a legendary bushie, who had supposedly lost a leg to a croc in an outback encounter. Linda Kozlowski, a relatively unknown US actor, played the role of journalist, Sue Charlton, and while she discovered that the story of Mick’s severed leg might have been exaggerated slightly, she fell for both the man and the remarkable Kakadu landscape.

At the time, Kakadu was better known as a mining site, with uranium at the forefront. In fact, such was the prominence of uranium that the region’s most famous tourism attraction – Gunlom Falls – was originally known as UDP Falls, because it was the early camp site of the Uranium Development & Prospecting Company.

Today, it is tourism that glows brightly for Kakadu, and the region owes a massive debt to Paul Hogan for bringing the Northern Territory outback region to international prominence.

While Paul Hogan may have been the face of the film, the man responsible for selecting the locations and transforming a relatively untamed landscape into a film set was a young man by the name of Craig Bolles, who was based in the Northern Territory and had a very thorough knowledge of the Top End and its almost secret sites.

Kakadu Tourism spoke to Craig about how a sparkle of idea in Paul Hogan’s mind translated into one of the most successful and visually significant films in Australian cinema history.

Film Director, Craig Bolles says:

“The location was terribly important for the success of the film. It showcased a part of Australia that I don’t think had been seen by most Australians, let alone foreigners, and it was inherent with Paul’s nature. He seemed to fit into the landscape perfectly.

“I was brought in as the location scout for the film because I’d spent a lot of time in the Northern Territory. I did all the location scouting for the film, then handed it over to a Location Manager and came in as Second Assistant Director for the film.

“I used to work for the Aboriginal Artist Agency during the late 70s/early 80s. I did a lot with local Aboriginal groups and spent a lot of time with them. I even learned to speak some of the language. We used to bring in touring groups for the Department of Foreign Affairs for their cultural exchange programme. I loved my time up there. I had a real passion for the Territory.

“I got into films via film called Manganinnie, which was a film about a Tasmanian Aboriginal woman who searches for her tribe with the company of a young, lost white girl. I got a call from a Producer saying could I organise a shoot for some Aboriginal actors, so I did that and it turned out to be a quite successful film, and because it dealt with wilderness and Aboriginal issues it led to me being contacted by the Crocodile Dundee producers.

“I had an open brief to choose anywhere in Australia that I thought suitable. I went across to the Kimberley as well, but in those days it was even more remote than Kakadu and I knew there would be a crew of 150 – 200 people, so I had to think of the logistics and Kakadu made more sense. Still, Kakadu was a very different place in the 1980s to what it is today. Only the main road was sealed and there were no hotel facilities at all as far as I can remember, just a few ‘dongas’.

“I just thought it was a great place because I had spent quite a lot of time there taking directors through the area for potential film shoots, including Jean-Jacques Annaud, who directed the film Quest for Fire. He was originally going to shoot that in Kakadu, so I spent a lot of time cruising around Kakadu looking for suitable settings.

“I always thought of Kakadu as an incredibly interesting and diverse destination, and as it had never really been showcased before, I thought it would be a great location to shoot Crocodile Dundee.

“Accommodating a crew of up to 200 in such an outback location was our biggest issue, but we had a stroke of luck early on. Initially I thought I would have to build the equivalent of a mining camp to house all the crew, but I was in a helicopter doing surveys and I asked the pilot ‘what’s that down there?,. and it turned out to be a mining camp that had never been used by miners.

“The Ja Ja Camp was set up by PanContinental Mining to house the workers for the proposed Jabiluka uranium mine, but the camp had never been occupied because they were waiting for approval from the Federal Government. So we landed the helicopter there and out came a manager with a shotgun and I explained what we were trying to do, He said the camp was ready to go and it could house up to 120 people, with five or six quite nice houses, plus a whole lot of dongas. It was perfect, so we contacted PanContinental and they agreed that we could lease it off them for the period of the shooting.

“The facilities were good. Paul Hogan had a four bedroom house with a massive dining room capable of seating 20 for dinner. It was set up for mining executives and full time workers coming in with their families, so it was pretty flash. Funnily enough, it was probably more sophisticated than Jabiru in those days.

“Finding the locations for the shoot wasn’t as easy as it may look today. For instance, UDP Falls (Gunlom) was connected by a dirt track that you wouldn’t find it you didn’t know where it was. Some old guy just told me the falls were down the track and it took me a few weeks to find the falls. There were a lot of uranium signs around there at the time, and some old uranium tracks – that was about it.

“Lots of these places were really hard to get to, but I went in there with a 4WD and cut roads where we needed to. I’d just fill up the car with food, lots of water, camp in the bush at times and it was incredible. In fact, I discovered lots of amazing locations, with beautiful waterfalls, that might have looked even better on film, but they were just too hard to get a whole crew into.

“When we filmed at Nourlangie, there were no barriers to the art galleries, just a track and you could walk around without any restrictions in those days. I’d just heard about these places through working with Aboriginal people and wandering around doing film survey work. I found galleries in there that are possibly more impressive that Nourlangie and Ubirr put together. I just never told anyone about them because they still had skulls and skeletons inside the caves so I just left them as they were because they were probably sacred sites.

“It was an amazing experience for the Paul, Linda and whole crew because the bush was very special, but it was tempered by the fact that they were surrounded by 150 people on a film set. The film shows a magnificently tranquil sunset looking out from Nourlangie, but the filming involved 120 people and all the hustle and bustle of a film set – it still looked magical on screen.

“Even filming at a relatively accessible location like Ubirr Rock – where we did the 360 degrees panorama – was a real ordeal because we had to carry in all the tracks and gear, and equipment was really heavy in those days.

“What was so wonderful then was that it was so remote. No one went up to the East Alligator River – we had to cut roads into there – but because I had spent a lot of time in Arnhem Land working with Gapuwiyak, I had a permit to go in and I knew quite a few people in Oenpelli.

“I had a 4WD and found the place along the Bardedjilidji Walk where we shot a lot of Crocodile Dundee 2, and just around the corner from there was an amazing art gallery in a cave where there were still full skeletons, but I obviously didn’t let anyone go near that.

“When I identified UDP Falls (now Gunlom) as a setting it was still very dangerous territory. We had to get someone into grade the track so we could get the trucks and buses in. In all the time we were there, we saw no one.

“We also had the problem that this was at the end of the dry season, and UDP Falls had virtually stopped flowing so we sent up half a dozen guys a few days before to ‘dam’ it so that when we did the big widescreen shots we actually had a good flow of water coming over.

“I found amazing places, almost better than that, but there was the whole croc issue where I had to be 100% sure they could swim in the pools without being eaten, because even when I was flying in the chopper we could see croc tracks in some bizarre places.

“We were so concerned we had a crocodile expert from Darwin and when we filmed the scene where the croc jumps out and grabs Linda’s water bottle we actually did that in a billabong very close to Darwin. It was called Girraween Lagoon, less than an hour out of Darwin, but as we had a mechanical croc and it involved lots of people, I didn’t want to drag that all the way down to Kakadu. But it looked pretty real.

“When it came to filming Crocodile Dundee 2 I actually said we should mix it up and go somewhere else. I suggested WA, a place such as the Bungle Bungles, because I wanted to create another look for it, but Paul and John Cornell were keen to go back to Kakadu, which is why I pushed into Arnhem Land and Cannon Hill…places like that to mix up the locations.

“I had a helicopter pilot called Shane – an ex hairdresser from Melbourne – who decided to become a helicopter pilot and we just hung out for quite some time and we’d go up looking for sites and I’d just see a spectacular spot and say ‘put me down there’. But there was no way we could have got everyone in there except by chopper, which just wasn’t feasible.

“Looking back at it now, it cost $8.6 million for Croc 1, which doesn’t sound all that much, but no one had any idea how it was going to be. Paul was quite a popular TV character in those days, but there was still considerable scepticism in the industry about how it would go. In fact, he took points rather than a wage, so did very well, because the film ended up grossing over $300 million.”

Craig Bolles was involved with all the Crocodile Dundee films and went on to be a very successful director of films, TV shows and advertisements.